If anyone is willing to help with the development of the project that would be wonderful. If so, email me at garry.barker@leeds-art.ac.uk and I can send more information.

The idea of using votives was something that initially occurred by accident. Approximately three years ago I had bad toothache but unfortunately I had not attended my six monthly check-up and my dentist had struck me off her list. I was temporarily without dentist and in pain. Whilst trying to solve my problem I made a small ceramic object to vent my frustration and when fired it gave me something to externalise my pain into, something I was able to do by squeezing it hard enough in my hand to hurt, and as the pain grew in my hand I was less focused on the pain in my mouth. Eventually a new dentist was sourced and the problem solved, my toothache object had a hole in it and I pushed it onto a nail in the studio wall and forgot about it.

A little while later I had an open studio exhibition concerned with age and several of the works exhibited were to do with what it felt like to be inside an ageing body. I had forgotten about the small object I had made in response to toothache, and it was still on a wall but well away from the exhibited work. However several people remarked on it, and when they discovered what it was made for, I quickly found out that I was not the only person to suffer from the loss of a dentist. I was then asked to make another of these ‘toothache cures’ and that evening I sold the one on the wall and could have done so several times over.

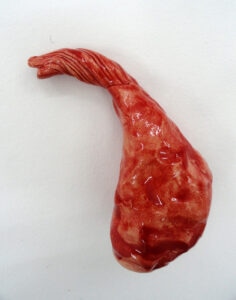

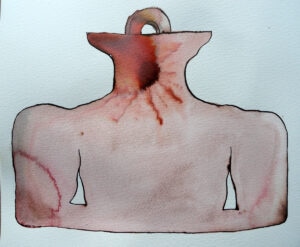

On making a new ‘toothache cure’ I was a bit more conscious as to what I was doing and it had a little more thought put into it, so the form began to evolve. Human communication can be rather like the child’s game of Chinese whispers, someone asked me to make them a ‘healing charm’, (a term I had never heard used before in relation to my work), they had a frozen shoulder that had not responded to medical treatment and on hearing about my toothache piece, wanted to see if an alternative approach would work. So I made a ceramic model for them and this time suggested that if they could externalise their pain or problem by putting it into the model I gave them, they would then have to ritually cast it away. I gave them three choices to smash it, hang it on a wall or give it away. They chose to hang it on a wall and within a few days they contacted me to say that their pain was rapidly going and that they were now moving their frozen shoulder much more easily and they had told other people about their experience.

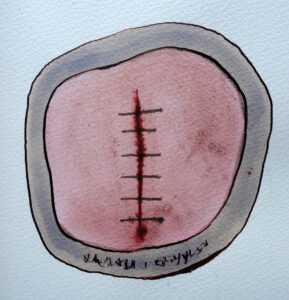

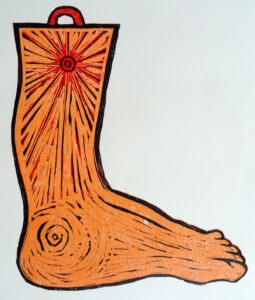

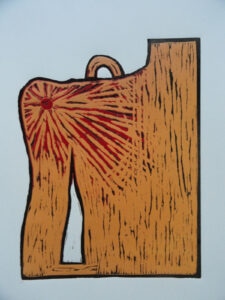

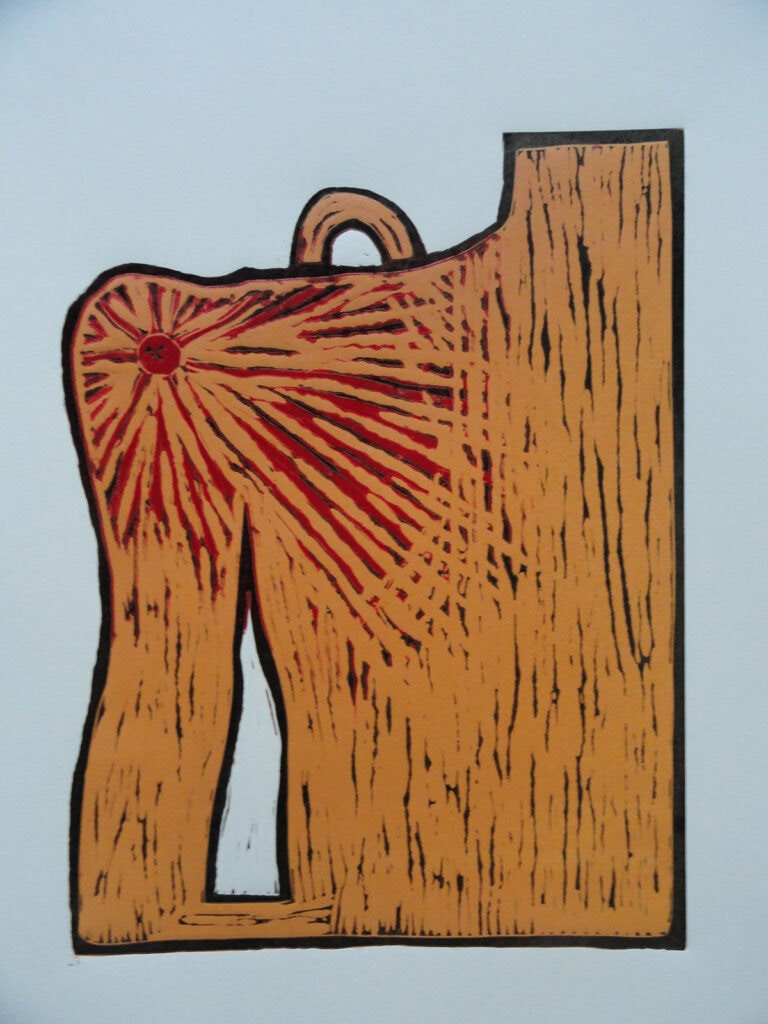

Frozen shoulders are a common problem amongst people of my age and friendship group, so because of a growing interest in what was happening, I made a linocut of a shoulder, this time with a graphic representation of radiating pain, thinking that printing was a faster and far cheaper way of making them. Only after I had cut the lino did I realise that I had included the half circular hanging hole that I had made for the ceramic version, a carry over that wasn’t of course needed in a print, but which somehow seemed appropriate, as it added to the quirkiness of the image, and was somehow also visually ‘painful’. However when it came to giving someone a print there was no ritual and so I had to invent one, and this took me back to Roman times. I had a couple years before had a project in York and during that time had made some drawings in the York Museum of an object that intrigued me and which I thought might be involved in some sort of ritual, so I decided to make my own version

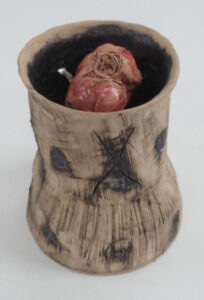

When someone needed to get rid of their print, I thought it would be a good thing to burn it and keep the ashes as a memory of the externalised and extinguished pain. I was still working out of my studio, a space that was located centrally in the community, therefore if people wanted something they came to my space. I set up a burner in my garden, so it could be used as ritual form of elimination, the smoke coming out of the top as the print caught fire, and as the oxygen was burnt away the fire went out leaving a now charred print, a print that I then realised had to be presented ‘properly’ as another part of a ritual exchange.

By now I was also making prints of other parts of the body because interest was growing, as well as more ceramic objects, in particular arthritis was a concern with several people I knew, including myself and I made some ‘arthritis’ hand pieces that had generated some interesting comments when shown in an exhibition. I also made ceramic containers for charred hand lino prints and one for feet prints. This seemed a much better way of presenting the end result. Again people seemed to value the trouble and time spent on them and although always ‘tongue in cheek’ they joked about how they always felt much better on seeing an image of their pain get burnt away, in fact they always wanted to be the person that lit the fire.

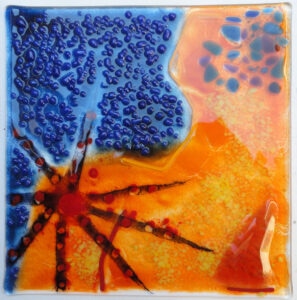

I began to explore other materials, fused glass in particular seemed an interesting area to explore as it had similar qualities to stained glass windows and the idea of light shining through an image seemed spiritually elevating. I had by this time become more aware of the historical precedents for what I was doing, and had been to the Manchester museum to look at their collection of votives, becoming by now very aware that this was what I was in fact making.

Other aspects of my art practice were becoming entwined into the process, for instance I make my own charcoal, and I saw a connection with the process of charcoal burning and the need to reduce the oxygen so that the wood was carbonised rather than burnt to ash and my burning prints ritual. So I made terracotta containers for the wood that went into the earth covered fire pit.

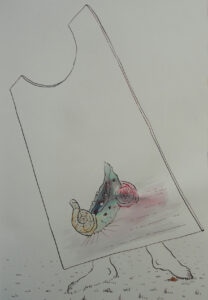

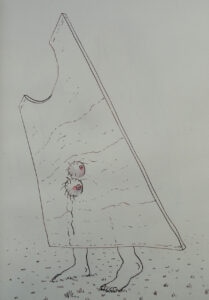

About a year ago the project took another turn and rather than a side issue it became a central focus of my practice. I had begun to work with people who had severe health issues, which were often causing other associated behavioural problems, such as difficulties in making social contact with other people and retreating behind closed doors. I had also realised that a large part of the work I had always done was about conversations and being a good listener. I would sit with someone for a long time while they talked and I drew or made things in clay in response to what I was told. Sometimes this was about how a pain felt, but at other times how it felt to be lonely or frightened or ‘crazy’ as one person put it. However what was perhaps more significant was that my long-term on-going interest in allegory and metaphor began to resurface. Several people spoke about how they saw their illness as part of life and as a metaphor for other things. For instance some felt that illness reflected their own inability to get a grip on life. People who had concerns about their role in the world would use body metaphors to explain this to me. Others talked about a failure to digest information, or an inability to see things clearly. They had poor taste or always felt as if they were off balance. I made things as we talked, and we would converse about how the things I made could represent these wider issues and gradually new material languages began to emerge.

Over this last year I have made objects that operate as metaphors and as direct substitutes for parts of the body. I have also been given a micro commission to look at the design and making of a set of votive cards that can be used to explore issues surround health and well being, in particular to help people begin to communicate about their health who find it hard to articulate things in words.

The work with cards is available here.

I continue to make ‘votives’ and to work with people to design various ways for them to externalise inner thoughts and feelings about themselves. I always begin conversations with a checklist of what we are doing and not doing. I make sure that people don’t confuse anything I am doing with any proper medical intervention, I make sure they realise that I am an artist and that as an artist my primary interest is in human beings and how they deal with stuff. I also begin a dialogue as to what they think the role of an artist could be and should be and how wide a definition an idea of what is beautiful might be. Part of this is to look at a process of acceptance and this is itself useful, because once both myself and the person I am working with accept that even difficult and painful things can be accepted as fascinating and wonderful parts of life, we can begin to face up to being alive more productively.

If anyone is willing to help with the development of the project that would be wonderful. If so, email me at garry.barker@leeds-art.ac.uk and I can send more information.